Curiosity as a Leadership Competency

“Curiosity killed the cat,” or so the old adage goes. Why does that phrase continue to come to mind when I think “curiosity”? Curiosity is a prerequisite for learning and an essential element of creativity. Yet there is much about the work environment of many organizations that kills curiosity.

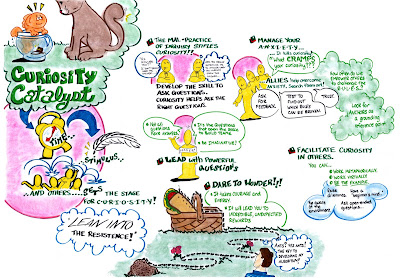

A few months ago my daughter, Jennifer, and I presented a workshop for General Mills ITQ (Innovation, Technology and Quality) Conference on leaders becoming more effective “curiosity catalysts”. (The mind map of our presentation done at the conference is below. ) One way we encouraged participants to promote curiosity is by leading effectively with questions. We discussed how the “malpractice of inquiry” stifles curiosity (and good, timely questions) again and again. An example of the “malpractice of inquiry” is when a manager asks a question and the answer has already been decided or so it seems to the group hearing the question.

MindMapping by Stephanie Crowley

Janet Rae-Dupree writing in last week’s Sunday NYT (“Can you Become a Creature of New Habits?) comments: “We tend to believe that those who think the way we do are smarter than those who don’t. That can be fatal in business…particulary with executives who surround themselves with like thinkers.” Regarding curiosity, she references the work of Dawna Markova, author of The Open Mind: “The first thing we need for innovation is fascination with wonder, but we are taught instead to ‘decide’…”. “You cannot have innovation unless you are willing and able to move through the unknown and go from curiosity to wonder.”

Just a couple of weeks ago I was visiting with Tim Cejka, President, ExxonMobil Exploration Company, in his office about the practice of “collective inquiry” in their organization. Their experience offers evidence that organizations can become creatures of new habits! “Collective Inquiry” is a meeting protocol now used by their leaders to signal explicitly a meeting designed to promote curiosity about technical issues that have enormous consequences. Learning is given priority over deciding in these meetings. Curiosity is expected and encouraged. The results have been tangible, including fewer dry wells drilled.

“Never lose a holy curiosity,” wrote Albert Einstein. Effective leaders know the value of curiosity.

One aspect of curiosity, particularly for scientists, is curiosity about how other disciplines can inform our thinking. Examples for me included two interesting a different publications: “Why Most Things Fail: Extinction, Evolution and Economics”, Paul Olmerod,J. Wiley & Sons, New York, 2005, and “Prospection: Experiencing the Future”, Gilbert and Wilson, Science, vol. 317, no. 7, September 2007. Both deal with howe think about the future and the role uncertainty plays. Sustained curiosity is one of the strategies for dealing with some of the forces the authros discuss.

Steve points out that “An example of the “malpractice of inquiry” is when a manager asks a question and the answer has already been decided or so it seems to the group hearing the question.” Another frequent problem is when one individual answers for a second individual. Inquiry is sometimes directed at an individual to get THEIR perspective, not he group’s perspective. I have seen situations where a question is directed at a junior member of a group but a “senior” member will sometimes speak before the junior member has a chance to present their own thoughts. This is one of the most frequent problems I observe in open discussions.

Steve,

I was just searching for articles on curiosity and leadership in order to help strengthen the link between ALA's values and leadership for our students, and the first site that appeared in my search was your blog! What are the odds? Thanks for the insights, and I hope all is well.

Warm regards,

Ngozi